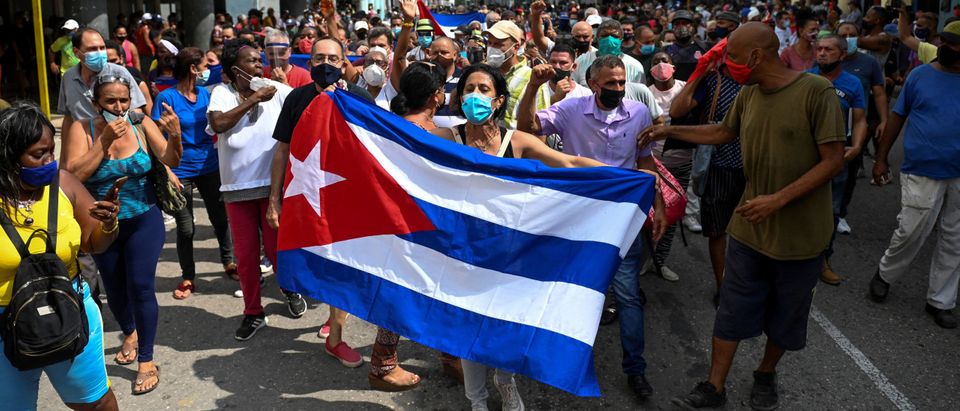

Though Cubans risk harassment and even death at the hands of Cuba’s brutal and autocratic regime, protests and cries for freedom continue to sweep the country. Unfortunately, bad-faith arguments persist, from the same people who routinely denounce trade as exploitative, that blame the U.S. embargo for Cubans’ discontent with their communist government.

Socialists aren’t exactly known for their love for unfettered markets. Free trade, in particular, is a frequent target of socialist critique. They frequently argue that free trade prevents developing nations from growing, and Karl Marx called free trade “shameless, direct, brutal exploitation” of the working class in The Communist Manifesto.

Yet when socialists talk about the embargo on Cuba, they suddenly become Austrian economists. Black Lives Matter (an organization whose leaders have long held Marxist views well to the left of the movement it is associated with), released a statement blaming the embargo for costing Cuba “an estimated $130 billion” and for destabilizing what surely would otherwise be a very stable and harmonious society.

The sentiment that Cuba’s loss of access to trade has harmed it is not wrong, even if according to import-substitution theory socialists often espouse elsewhere this should have allowed Cuba to develop a flourishing domestic industry free from American dominance. What makes it so odious is the implication that it’s solely responsible for the discontent of the Cuban people.

The growth of global trade has been the greatest global anti-poverty program ever conceived of. In the twenty years following the fall of the Soviet Union and the ensuing opening up of markets across the world, the number of people living in extreme poverty was cut in half. At the same time, developing countries’ share of global trade grew from 33% to 48% between 2000 and 2011.

Latin American countries broadly have experienced significant progress in eliminating extreme poverty, with the extreme poverty rate dropping from 14% to 4% between 1990 and 2015. Cuba’s rate of extreme poverty, however, remains around 15%. The average Cuban worker earns between $17 and $30 a month in U.S. dollars, an amount which is below the extreme poverty line.

Undoubtedly some of this destitution is due to the country’s reliance on state-run enterprises and restriction of private property rights. But Cuba has been effectively cut off from much of the global economic growth that the era of globalization has brought the world.

Embargoes are a tool to achieve foreign policy goals, not economic ones. But while socialists and apologists for Cuba’s repressive regime are correct to argue that this particular embargo has had significant consequences for Cuba’s economy, it’s hard to believe that they truly grasp the argument they’re making here. After all, if they understood the degree to which trade liberalization has been an unmitigated success at ameliorating global poverty, then surely they would support it.

Socialists may accidentally have stumbled upon a good point when they argue that trade barriers prevent poor nations from developing. It’s just not the point they think it is.

Andrew Wilford is a policy analyst with the National Taxpayers Union Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to tax policy research and education at all levels of government.